The Wholeness Formula

There is a formula for happiness that appears in many literary works and traditions. The basic of the formula is to justify the disdain for strife by attempting to perceive strife, or misery, as part of a whole that contains the things we appreciate in life. I will call this, the “wholeness formula.” It seems intuitive that if a person can apply this formula to his or her attitude toward the world it would achieve happiness. The difficulty lies in how one would successfully apply this formula to his or her attitude

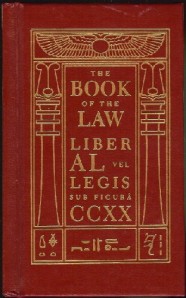

In Liber Al Vel Legis, the main Holy Text of Thelema, we find a method for training oneself to accept this attitude. The text instructs readers to identify simultaneously with the goddess Nuit and the god Hadit. Nuit and Hadit are lovers. Thus the reader is expected to identify with the lover and the loved. Hadit is said to represent any specific point in the universe and Nuit the totality of possibilities in the universe.

Nuit speaks in Liber Al. saying “I am divided for loves sake.” Thus the romantic exchange between the one who desires and the desired are part of a felix culpa that allows for love. It is the totality of the situation that makes the joy possible. The separation is part of the whole. To meditate on these symbols is to attempt to teach oneself to experience the wholeness formula for happiness.

Why the romantic metaphor? It hurts so good!

By my interpretation the romantic metaphor is used to evoke a set of feelings we can identify with that we may attempt to apply to our goals for our attitude change. People engage in feats of patience and resolve in order to pursue their romantic love. Many songs depict working hard and long-hours joyfully to make a life with a beloved.

John Mellancamp sang “Hurts so good. Come on baby make it hurt so good. Sometimes love don’t feel like it should. Babe it, hurts so good.” The pain associated with his love is paradoxically part of the good feeling. The beard-stroking-term I would use for this would be “didactic metaphor.” A didactic metaphor is a metaphor used to teach something. Often didactic metaphors are used in literature, ritual, or meditation, to evoke certain attitudes. Liberal al, encourages us to use the didactic metaphor of Nuit and Hadit in our rituals and meditations.

The Biblical Story of Job

Job does nothing but good and praises God. But the devil dares God to test Job’s faith by doing all kinds of horrible stuff to him. Long story short, Job’s family dies, and he ends up homeless and covered in open sores. But Job stays faithful almost all the way through. Then at the very end Job cries out asking why God would let all these bad things happen to him. God then chews Job out for not appreciating him. Saying something to the effect, “I created the universe. I call the shots beeyotch.”

In a modern context this can be taken as a deeply upsetting story of abuse. But since the more direct application of didactic metaphor I found in Liber al, I have begun to see this as an application of the wholeness formula.

Did Job grow up in Game of Thrones?

In the time of writing the bible tribal conflicts were common place. Normal life was likely subject to rigid rules we would today consider more appropriate to the military. A tribal leader who would exact cruelty, quickly and without warning, would command the respect necessary to maintain battle-ready military order. Perhaps a reputation of this kind would be useful even for keeping potential invaders at bay. (In the first season of Game of Thrones, Eddard Stark observes rules of authority with a similar rigidity. The order is kept even when it seems unfair, because it protects the realm.)

But the subjects of such a leader would need to learn to love and respect the tribal leader whatever cruelty he would exact. The love and respect of the leader would be essential to survival. So the metaphor of God representing the cruel and fickle forces of the universe, as something we must learn to love, is analogous to seeing the misery and pain as part of the pleasure and joy of the whole. Thus it was an application of the wholeness formula.

We couldn’t have the safety of a fierce tribal leader without the cruelty. It was part of the whole. Thus when contemplating the cruelty exacted by the universe, a person in the time of the old testament may have sought his comfort, by learning to see it as coming from the same hand as the joys of the universe. It would have been a more accessible metaphor.

Sincerely,

Alexander the Zounderkite

1. What do you folks think?

2. Can you come up with any traditional, or New Agey, passages with potential didactic metaphors?

3. Are you hoping I will get over this metaphors-of-the-bible stage soon?

4. Are you proud of me for hitting this month’s blog deadline?

Please criticize my writing. I don’t want my brain to turn to mush.

I feel like your argument starts out with a serious flaw. Primarily, you compare literary works to real life. They are not like things, and that is why it’s so practical to apply that formula to literature, while not applying it to real life. Because a story is not the thing itself. Even a story about myself where I overcome an obstacle and have a greater appreciation for good things in life is not as it is in literature. Because I will continue to live, and lose the thread of that particular plot in the greater story of my whole life, with all its insomniac nights and sitting in traffic and selling movie tickets and feeding my cat. The release we feel after overcoming a major obstacle or gaining a satisfying achievement is so temporary compared to a plot in a story. Like Job. In his story, he will always have overcome that time of suffering where he lost it all. And, to us, he will always be experiencing the multiplied blessing of having overcome that suffering. Because that’s where his story ends.

The only way I feel like a story or a song can be complete is when its main speaker is dead, which is considered by many writers to be a form of “cheating”, by taking away the reader’s chance to imagine the ramifications of the story on the character after the tale ends. And, bringing in Game of Thrones, that is one interesting aspect of the story…because main characters often die, but there are so many threads of the story that all achievements may be brought to nothing, and all plights may be overcome and the reader can carry on, but aside from that multiplicity, it’s much more relatable to real life because of the constant alternations between triumph and defeat, and the uncertainty that takes away contentment and replaces it with anxiety.

But, maybe I missed your point entirely.

I’m confused by the connection to your comment and my post. Are you disagreeing with the didactic metaphor I attribute to Job?

Do you mean to say the purpose of Job is that he survives past that? This post was originally titled, “Why the Liber Al Vel Legis made the old testament God not look so bad.”

Perhaps that was a better title. Because really my interpretation focuses on the meaning of the deity in the story. The questions “Why does the deity censure

job for being frustrated with his poor treatment? Why would an author put that into a story?” were more the focus of my exploration.

“. Primarily, you compare literary works to real life. ”

What do you refer to?

When I write short stories the main character almost always dies. I had a daydream of writing a collection of short stories, that the main characters die so often that the reader becomes surprised when a main character survives a story. 🙂